Everything NIST compliant DoD Contractors Need To Know Now That CMMC Version 1.0 Is Out!

Everything NIST compliant DoD Contractors Need To Know Now That CMMC Version 1.0 Is Out!

The Office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition & Sustainment released the much anticipated CMMC (Cybersecurity Maturity Model Certification) version 1.0 just weeks ago, giving those of us in the cybersecurity community a few weeks to digest the final version and get to work applying it in the real world. Stronghold Cyber Security works primarily (but not entirely) with defense contractors who need assistance protecting their CUI (Controlled Unclassified Information), CDI (Covered Defense Information) and FCI (Federal Contract Information) in accordance with DoD regulations. Compliance is always a minefield, and its really best best to work with SME’s (Subject Matter Experts) to ensure firstly that contractors are actually compliant, and secondly, not saddled with unnecessary costs or negative operational impacts in so doing.

Most of the DIB (Defense Industrial Base) will fall under CMMC Level 3, particularly those contractors who who fall under NIST 800-171 and DFAR 252.204.7012. NIST 800-171 contains 110 requirements (controls) spread over 14 families. The first step to compliance is developing an SSP (System Security Plan) which enumerates each of the controls and explains if/how the contractor is in compliance.

On top of the 110 controls in NIST 800-171, the CMMC Level 3 imposes 20 new “practices” (which are really just controls), spread out over 15 capabilities. Out of these 20 new CMMC practices, 8 of them either augment or enhance the controls in 800-171, and 12 of them are entirely new. Five of the 20 CMMC Level 3 practices require technical controls which are not present in NIST 800-171; namely in the form of e-mail protections, DNS filtering, and resilient backups.

So, lets go through these 20 new CMMC practices one by one, and have a brief discussion about what each of them means in easy to understand terms.

AM.3.036 — Define procedures for the handling of CUI data.

This practice is an enhancement to NIST 800-171 3.1.3 which reads “Control the flow of CUI in accordance with approved authorizations.” These two requirements should be addressed in tandem. The CMMC provides some examples here:

• identification of CUI when provided government labeling and guidance;

• controlled environments to protect CUI (e.g., put it in a designated system or folder);

• steps to reasonably ensure that unauthorized individuals cannot access CUI; and

• protections for the confidentiality of CUI (e.g., electronic or physical CUI when in transit

So, contractors will need to have comprehensive policies and procedures for the handling of CUI data, and also make sure their employees are properly trained.

AU.3.048 — Collect audit information (e.g., logs) into one or more central repositories.

This practice is an enhancement to the whole of NIST 800-171 3.3 (Audit and Accountability), which effectively requires a SIEM (Security Information & Event Monitoring). Any SIEM that is worth its salt is going to have the capability to do this. If you are meeting the 9 controls in section 3.3, you are almost certainly meeting this. That said, out of the dozens of SIEM offerings on the market, it is important to make sure that the SIEM you choose is meeting both NIST and CMMC requirements.

AU.2.044 — Review audit logs.

This practice is another enhancement to section 3.3. A SIEM is not “set it and forget it”. Someone on your security team must be formally tasked with reviewing audit logs at least weekly, or whenever anomalous activity is detected. This review activity should also be recorded into a ticketing system or similar, for review by CMMC auditors. They may ask contractors to prove that they are reviewing the logs as required.

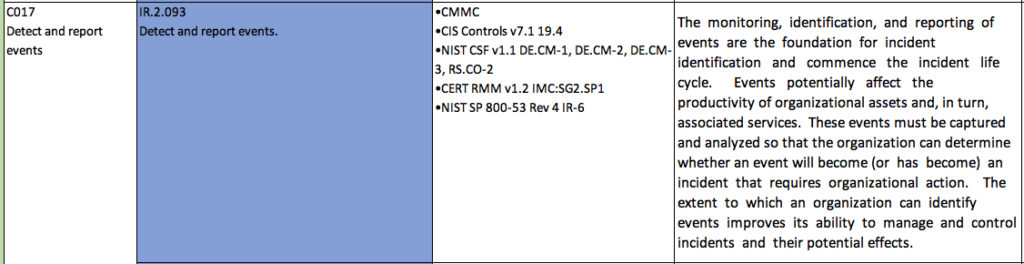

IR.2.093 — Detect and report events.

This practice is for the most part an enhancement to 3 of the families in NIST 800-171 which prescribe SIEM, IDS (Intrusion Detection), and Vulnerability Scanning. We usually find during assessments that contractors are missing most or all of these, and recommend a UTM (Unified Threat Management) solution. The UTM must not only be configured to detect the events, but notify the correct security team members, who must in turn respond when appropriate.

IR.2.094 — Analyze and triage events to support event resolution and incident declaration.

NIST 800-171 has 3 controls which speak to Incident Response. IR.2.094 is an enhancement to this process, instructing contractors to: “Categorize, prioritize, or group events to determine how to handle the event.” In the event of an incident, contractors are further instructed to:

•declare an incident from the event;

•escalate it to someone outside the organization; and

•close the event because it does not have a large consequence on the organization

These response activities should also be recorded into a ticketing system or similar, for review by CMMC auditors. They may ask contractors to prove that they are actually following their incident response plan, and that it is not just paperwork that exists for the sake of existing.

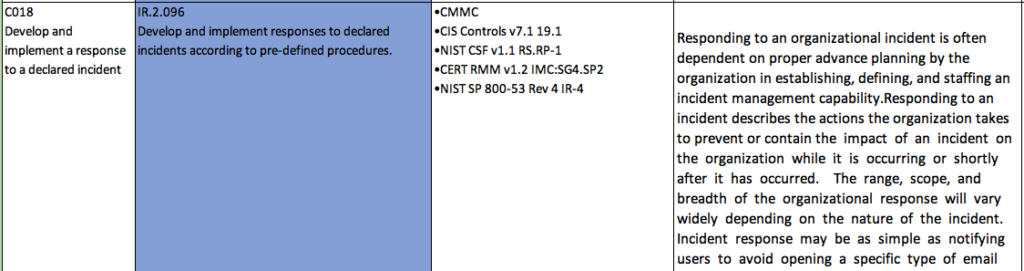

IR.2.096 — Develop and implement responses to declared incidents according to pre-defined procedures.

A boiler plate IRP (Incident Response Plan) that exists for the sake of satisfying the framework is no longer good enough — the CMMC expects contractors to do advanced planning by anticipating what kind of incidents they might expect, and then writing responses to deal with them ahead of time. These pre-written responses might include:

•stopping or containing the damage (e.g., by taking hardware or systems offline);

•communicating to users (e.g., avoid opening a specific type of email message);

•communicating to stakeholders (e.g., corporate management); and

•implementing controls (e.g., updating access control lists).

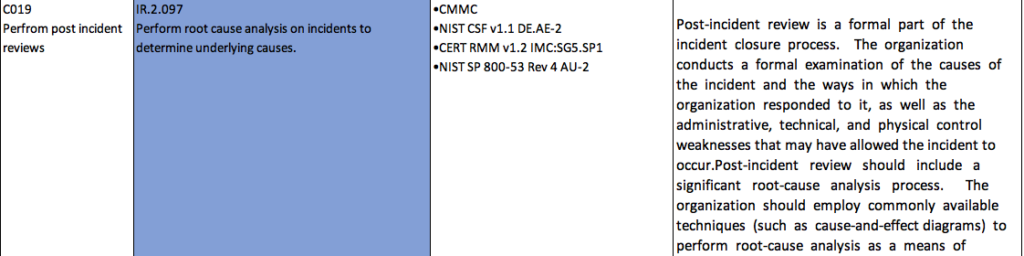

IR.2.097 — Perform root cause analysis on incidents to determine underlying causes.

Emphasis on maturation of Incident Response continues with this practice. Contractors are expected to determine what happened during an incident, and why. The practice further instructs: “Use available practices, such as cause-and-effect diagrams, to perform root-cause analysis. This will prevent future similar incidents. After incidents are resolved, conduct reviews and capture lessons learned. Make improvements based on the outcomes of these activities, such as updating plans or controls.”

Once again, these activities need to be recorded somewhere for possible review by CMMC auditors.

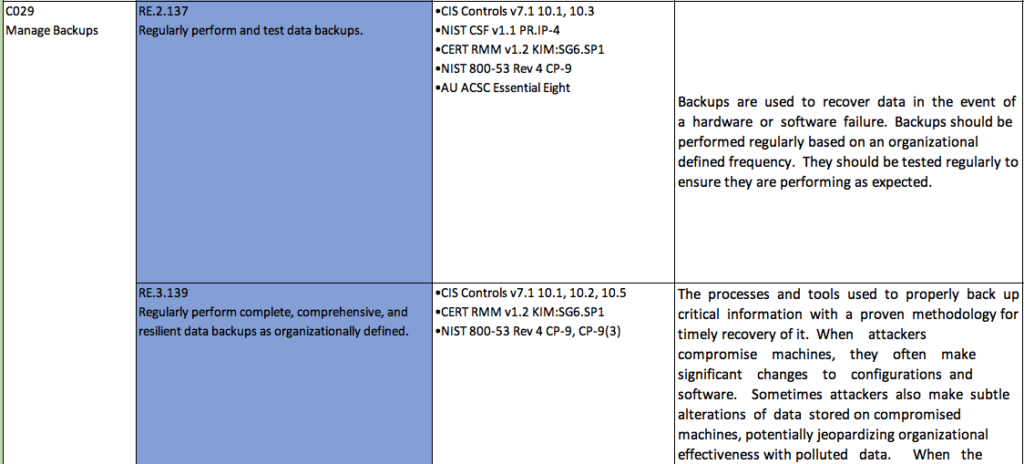

RE.2.137 & RE.3.139 — Regularly perform and test data backups, Regularly perform complete, comprehensive, and resilient data backups as organizationally defined.

These two practices go hand-in-glove, so we’ll address them together. While performing and testing data backups has long been considered a cybersecurity best practice, there was no requirement under NIST 800-171 to perform backups. This changes with the CMMC. Contractors are expected to have backups that can withstand human error, natural disasters, hardware & software failure, etc. AND to actually follow a regiment of testing these backups. Also keep in mind that FIPS validated encryption must be used (AES-256, for example) and that access to encryption keys must be controlled.

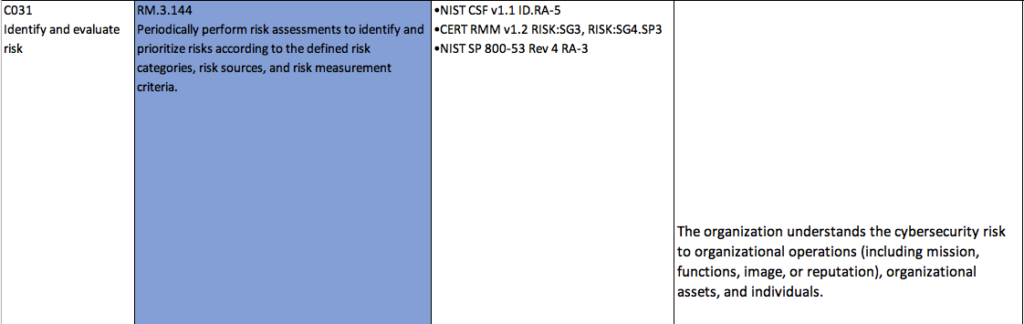

RM.3.144 — Periodically perform risk assessments to identify and prioritize risks according to the defined risk categories, risk sources, and risk measurement criteria.

This practice does not create any additional requirements beyond NIST 800-171; this is pretty much the same as control 3.11.1, with the exception that 3.11.1 specifically mentions CUI. For small companies, we provide a Risk Assessment Template as part of the SSP, which can be completed as a table top exercise. Larger companies should do a full blown Organizational Risk Assessment using NIST SP 800-30 (Guide for Conducting Risk Assessments).

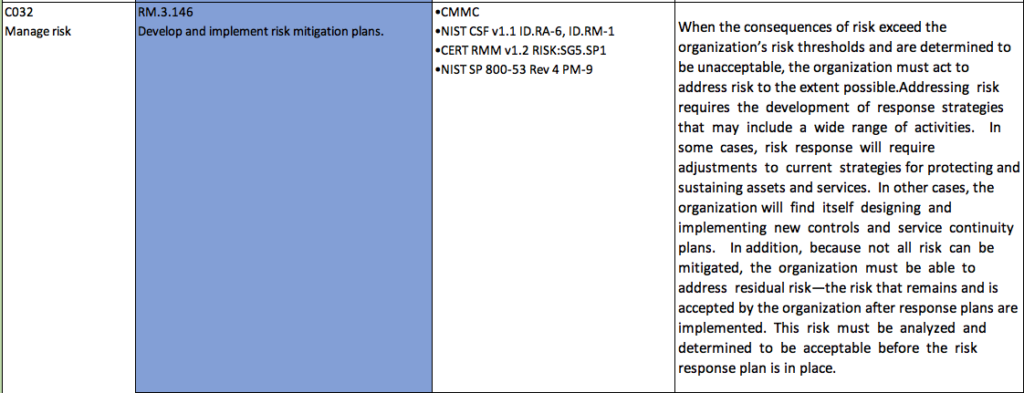

RM.3.146 — Develop and implement risk mitigation plans.

Not only do contractors need to be aware of some of their organizational risks, they need to have a written plan to respond to them should a threat actually materialize. Risk mitigation plans may include:

•how the vulnerability or threat will be reduced;

•the actions that will limit risk exposure;

•controls to be implemented;

•staff responsible for the mitigation plan;

•the resources required for the plan;

•the implementation specifics (e.g., when, where, how); and

•how the plan implementation will be measured or tracked

Meeting this practice is going to come in the form of written policies and procedures that must be actually followed, and continuously updated and improved.

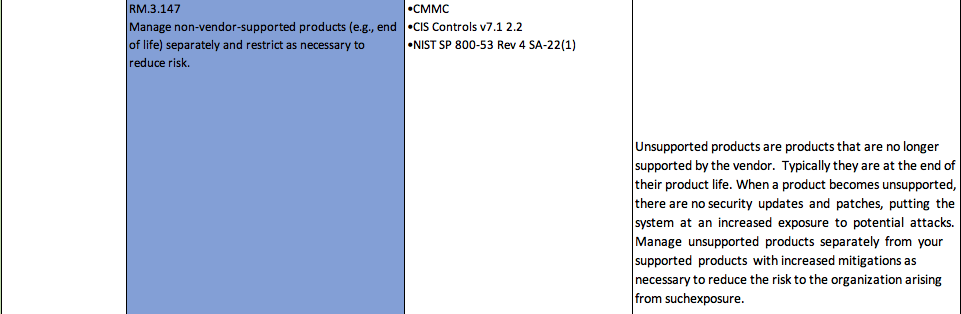

RM.3.147 — Manage non-vendor-supported products (e.g., end of life) separately and restrict as necessary to reduce risk.

This practice openly recognizes one of the shortcomings with NIST 800-171 — that framework does not go far enough in addressing old or unsupported systems which are quite common in the manufacturing sector. When doing assessments, we see a lot of XP embed running machinery, old Linux kernels, etc. Manufactures cannot simply get rid of these things. RM.3.147 should be considered in tandem with NIST 800-171 3.13.4, which states: “Prevent unauthorized and unintended information transfer via shared system resources.” That control was intended to deal with legacy systems using old file systems like FAT-16 and non-ring-mode kernels, for example.

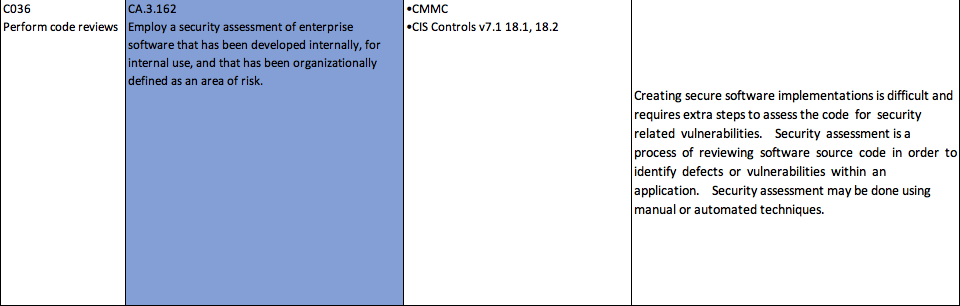

CA.3.162 — Employ a security assessment of enterprise software that has been developed internally, for internal use, and that has been organizationally defined as an area of risk.

This practice augments NIST 800-171 3.13.2 which briefly touches on software development. It’s not unusual for contractors to be employing various types of proprietary software in their operational environments. Contractors need to be doing formal code reviews and following a recognized secure software development methodology.

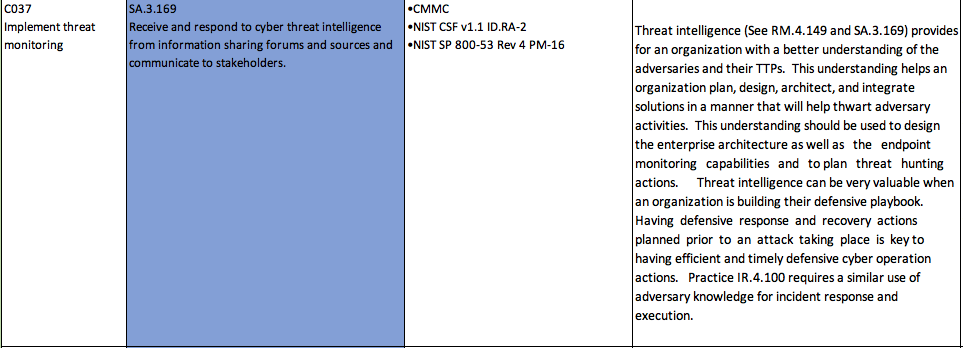

SA.3.169 — Receive and respond to cyber threat intelligence from information sharing forums and sources and communicate to stakeholders.

This practice augments NIST 800-171 3.14.3, which states: “Monitor information system security alerts and advisories and take appropriate actions in response.” When writing System Security Plans, we generally advise our clients to start by subscribing to alerts from CERT, NVD, and Security Focus, in addition to vendor alerts for vendors they are heavy on. During the entire process of complying with the CMMC, most contractors are going to require a UTM (Unified Threat Management) type device to handle SIEM, IDS, and vulnerability scanning. The vendors of these devices (at least the good ones) will typically provide a threat intelligence feed, as do the more advanced endpoint protection services. Contractors can also subscribe to feeds from (for example) DHS, SANS, Virus Total, and others. SA.3.169 also goes on to say that this information needs to be shared out with organizational stakeholders when deemed appropriate. For example, if some kind of known threat activity creates additional risk for specific businesses which include you, this information needs to be conveyed to others.

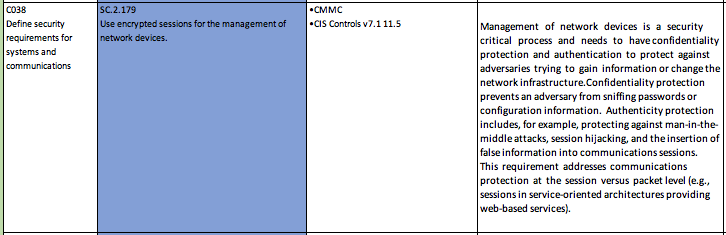

SC.2.179 — Use encrypted sessions for the management of network devices.

This practice works in tandem with several other controls already in NIST 800-171 (3.5.10, 3.13.8, 3.13.3, 3.13.11, 3.13.15) which require C.I.A. (Confidentiality, Integrity, Availability), plus FIPS validated encryption for network communications. During assessments, we nearly always find older clear text protocols such as telnet and FTP running on our clients networks. SC.2.179 is essentially reinforcing the requirement that contractors are not using insecure protocols to administer routers, switches, firewalls, etc. There are many reasons we run network scans using Nessus for every single security project we do, and this is one of them.

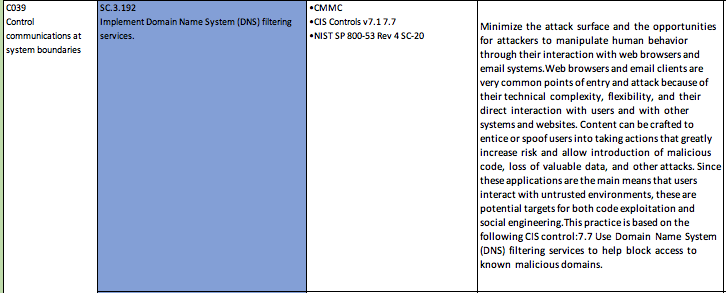

SC3.192 — Implement Domain Name System (DNS) filtering services.

This practice is an entirely new requirement beyond anything prescribed in NIST 800-171, and is very specific. The practice clarification tells us everything we need to know here: “This practice is based on the following CIS control:7.7 Use Domain Name System (DNS) filtering services to help block access to known malicious domains.” This is a very common practice in the IT security realm, and even many cheap consumer grade routers support this type of function.

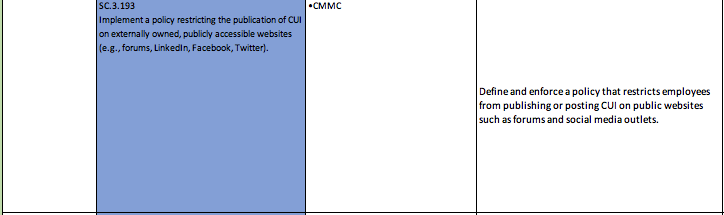

SC3.193 — Implement a policy restricting the publication of CUI on externally owned, publicly accessible websites (e.g., forums, LinkedIn, Facebook, Twitter).

This practice supplements NIST 800-171 controls 3.1.3 and 3.1.22, which speak to controlling the flow of CUI, and the posting of CUI on public information systems. SC3.193 takes this a step further and states explicitly that contractors need to ensure that their employees are not posting CUI on websites or Social Media. This will require contractors to have written policies and procedures, and for employees to sign off on them.

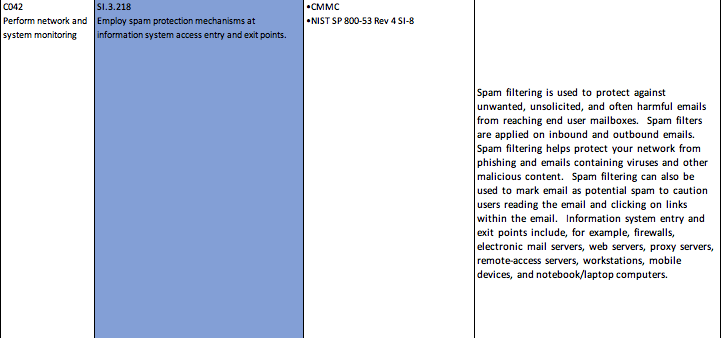

SI.3.218 — Employ spam protection mechanisms at information system access entry and exit points.

This practice is an entirely new requirement beyond anything prescribed in NIST 800-171, and is (like SC.3.192 ) very specific. E-mail is still a very common bad-guy attack vector, therefore contractors need to employ e-mail spam protection mechanisms at information system access entry and exit points.

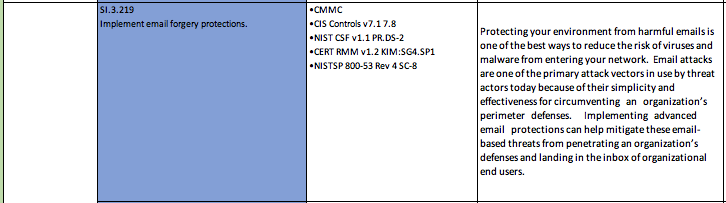

SI.3.219 — Implement email forgery protections.

This practice is also an entirely new and very specific requirement beyond the controls in NIST 800-171. Contractors need to implement anti-forgery technology on their email platforms. This will help to reduce the effectiveness of phishing, spear phishing, and whaling attacks, among others. There are many vendors who provide this service.

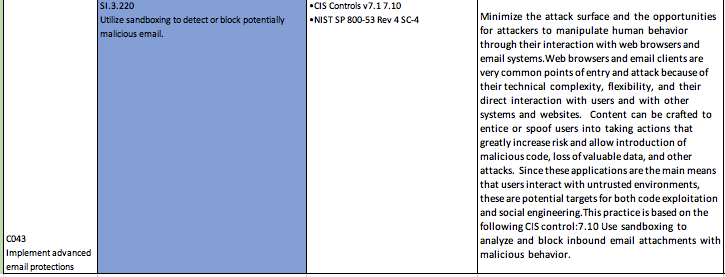

SI.3.220 — Utilize sandboxing to detect or block potentially malicious email.

This is another practice that goes beyond anything prescribed in NIST 800-171. Contractors need to employ technology which can effectively quarantine any e-mail which is suspected of having a malicious payload, until a human reviews it and takes an action to release it. There are many e-mail security vendors that offer sandboxing capabilities.

Conclusion

If contractors are already NIST 800-171 compliant (which they were supposed to be by the end of 2017), then turning things up a bit to get CMMC ready wont be terribly difficult. As mentioned above, out of these 20 new CMMC practices, 8 of them either augment or enhance the existing controls in 800-171, and only 12 of them are entirely new. Five of the 20 CMMC Level 3 practices require technical controls which are not present in NIST 800-171 at all; namely in the form of e-mail protections, DNS filtering, and resilient backups.

As of writing this blog, I have already gone through adding the CMMC controls to a handful of existing SSP’s, and it took on average 10-12 hours (I am an expert at this however) including a 1-2 hour interview with the client. The results were mixed, with some clients already meeting some of the new controls, and others having several new items on their POA&M’s.